by Susan McCaslin

From our new website section, Perspectives…

“You may say I’m a dreamer

but I’m not the only one

I hope someday you’ll join us

and the world will be as one.”

John Lennon from “Imagine”

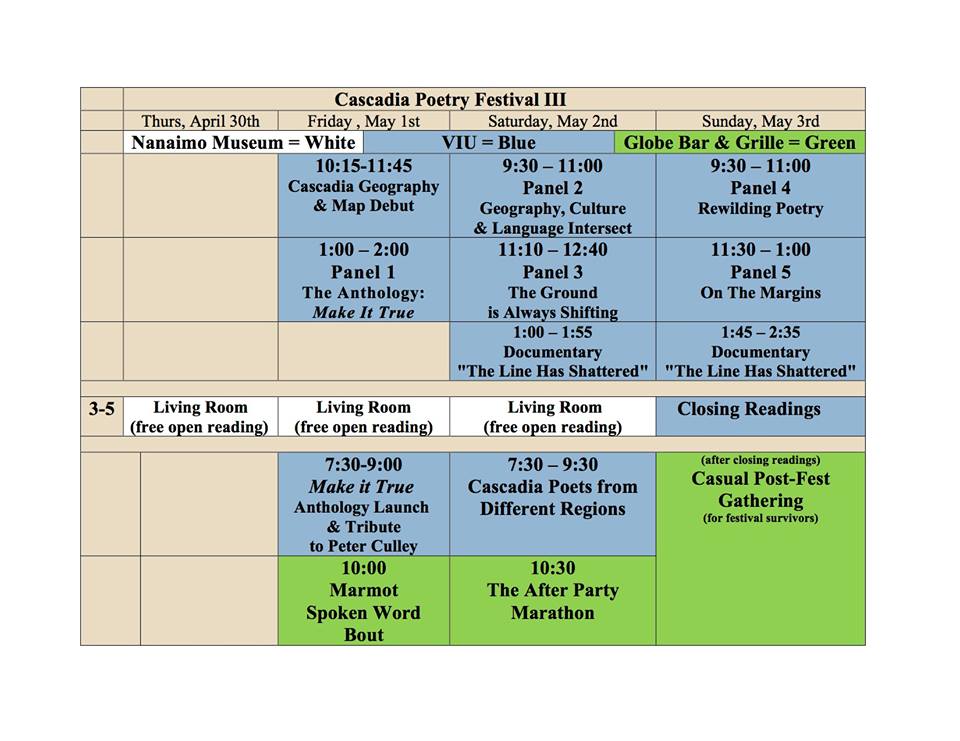

The Cascadia Poetry Festival in Nanaimo, British Columbia (April 30-May 3, 2015) was a rich conjoining of ecologically-minded poets from the States and Canada who identify with the richly diverse bioregion named Cascadia that stretches from southeast Alaska to northern California. The premise of the conference was that our common grounding in the land—in place—allows us to transcend political lines and demarcations; that as poets, we are part of the larger ecosystems that flow within and through us. David McCloskey, geographer, and founder of the Cascadia Institute, presented a map of Cascadia, decades in the making, delineating the geographic history of this bioregion. David spoke eloquently of how sea, land and sky form an integral unity.

A related theme of the conference had to do with “linguistic mappings.” B.C. poet Robert Bringhurst, known for his translations of Haida epics, observed that languages are ecosystems, revelations of the ecologies of the earth. He proposed that school children should be taught at least one aboriginal language. These indigenous languages, he urged, need to be preserved not only for First Nations communities but for all. Entering into the language, myths, and stories of the First Nations could deepen our ways of seeing, knowing, and being in the world.

While I applauded I thought to myself: now we’re into big, deep-time dreaming. During the response period, I commended Robert for his thesis, but questioned whether such a proposal might seem “utopian” to many, especially in light of the current cuts to education in BC. I could practically hear my daughter, a young educator in the BC school system who worked with aboriginal children as a tutor, saying: “I’d love to see this happen, but it’s not very likely right now. Maybe we could start by introducing kids to more of the indigenous myths and stories.” Bringhurst pointed out that aboriginal languages are already being taught in some Canadian universities. His response reminded me that big dreams and visions begin with incremental steps. The focus needn’t be on near-term outcomes, but on doing what must be done to bring about restoration. Okanagan poet Harold Rhenisch commented that Cascadia has long been a place of utopian colonies and dreams.

When I taught English at a community college in the lower mainland of B.C., I offered a course on dystopian and utopian literature. Dystopian literature explores recognizable terrains of hellish enclosure. George Orwell’s 1984, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, and Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy spring to mind.

Yet it is utopian rather than dystopian literature that continues to draw me in: Plato’s The Republic, Sir Thomas More’s Utopia, William Morris’ News from Nowhere, and Ursula Le Guin’s Always Coming Home. The inventory stretches on. Despite utopian imaginings and actual experiments, we haven’t had the kingdom of heaven on earth, at least not for any great length of time. When Plato tried to enact historically the ideas expressed in his Republic, Dion of Syracuse, the young man he trained for the job of being the first philosopher king, morphed into a petty tyrant. Plato’s utopia seemed flawed to me because it excluded the poets. The notion of philosophers ruling appealed, but only if they lived up to their names as “friends of wisdom.” More often the adage “power corrupts” seems to apply.

One question I’ve pondered for decades is: Why do utopian experiments generally fail? From Brook Farm in nineteenth-century New England, to Coleridge’s dream of Pantocracy, to the Finnish utopian community of Sointula on Malcolm Island off Vancouver Island (founded 1901), these forays into in alternative living generally fall prey to economic crises, clashing egos, power hunger, and cultishness. In a recent documentary written and directed by Jerry Rothwell on the Greenpeace movement, How to Change the World, what fascinated me was not only the amazing story of how a small group of activists succeeded in stopping the whale hunt, but how the various leaders soon fractured into vying factions.

Some might say the problems all come down to “human nature,” meaning the propensity of humans to act out of egotism, self-centredness, greed, and the desire for power rather than empathy and a sense of commitment to the public good, not just the public good for humans, but that of other species and the planet. Ecological poets sense these various dimensions can’t be separated. I’m not the only one to feel that the human species is in the middle of a collective crisis where we either transform and reverse our mass destructiveness, or hasten our extinction through our desire for unlimited development.

Even though utopias mostly fail, we require the unfettered utopian imagination. Environmental activist and Buddhist teacher Joanna Macy speaks of “a great turning” where humans might join together to put their creative energies, their collective imagination for a better world into action. I don’t know whether we have reached a place where it’s too late to turn things around, but, whatever the case, we have to try. Big dreaming isn’t based on prediction or certainly, but on envisioning alternative realities. The capacity to counter-dream the cultural malaise is innate. William Blake proclaimed, “Imaginary things are real.” What I think he meant is that if you can imagine something, it is a perceptual reality in some dimension of being. We live not knowing outcomes, but with awareness that how we act and how we choose to be matters.

Etymologically, the word utopia means “nowhere,” not a topos or place. A cynic might counter that utopias are projects based on wishful thinking. Yet another way of looking at “nowhere” is that it is a place that begins within the heart (so is at first invisible) but reaches everywhere. Some think of utopian notions as mere mental constructs, abstract, static, and unrealizable. But what if utopian visions of nowhere are indeed everywhere, forged in the heart and reified in the bloodstream? Perhaps true utopias aren’t plucked from beyond, out of the sky, or out of our heads, but arise within us through our connection with the earth itself. Perhaps they aren’t idealized places free from conflict but places where creative energy lives within the tensions and paradoxes in order to forge newness. If this is so, then utopia might just be the “no place” that is a “here and now place” within consciousness and within the world. If we walk into the woods, the forests, into what remains of wilderness, we might begin once again experience the world directly and realize that it is we who have removed ourselves from paradise. From there the journey home might begin.

“Poetry makes nothing happen,” a statement by W.H. Auden often lifted out of context, can be misleading. Poetry consists of words and language at their most vital— lamenting, praising, singing— and has the capacity to change everything. We have the desire and the need to place our creative gifts, our offerings, among the orders of the other creatures and larger eco-systems to which we belong. We all have poetry in our mouths and in our bones. The first cry of an infant is a poetic utterance, an om of being containing all sounds. Our poetic yawps and howls are participations in the poem of the world, a mystery which is constantly emerging out of silence into fuller articulations of being-in-the-world.

Susan McCaslin is a Canadian poet who has published thirteen volumes of poetry, including The Disarmed Heart (The St. Thomas Poetry Series, 2014), and Demeter Goes Skydiving (University of Alberta Press, 2011), which was short-listed for the BC Book Prize and the first-place winner of the Alberta Book Publishing Award (Robert Kroetsch Poetry Award). She has recently published a memoir, Into the Mystic: My Years with Olga (Inanna Publications, 2014). Susan lives in Fort Langley, British Columbia where she initiated the Han Shan Poetry Project as part of a successful campaign to save a local rainforest.

Susan McCaslin is a Canadian poet who has published thirteen volumes of poetry, including The Disarmed Heart (The St. Thomas Poetry Series, 2014), and Demeter Goes Skydiving (University of Alberta Press, 2011), which was short-listed for the BC Book Prize and the first-place winner of the Alberta Book Publishing Award (Robert Kroetsch Poetry Award). She has recently published a memoir, Into the Mystic: My Years with Olga (Inanna Publications, 2014). Susan lives in Fort Langley, British Columbia where she initiated the Han Shan Poetry Project as part of a successful campaign to save a local rainforest.

Hi Paul,

Just thought I’d let you know that, as Robert Bringhurst rightly pointed out when he responded to my question from the audience at the Cascadia Poetry Festival, bringing indigenous languages and world views into the education system is happening right now in universities in Canada. So the notion isn’t as “utopian” in the pejorative sense (as unrealistic or difficult) as it might seem. It’s happening now. See this article that appeared in today’s Vancouver Sun where Wab Kinew is quoted extensively:

http://www.vancouversun.com/life/Aboriginal+leader+calls+indigenous+education+initiatives/11053412/story.htmlMyCl

Is there a way to post my above remark about this issue with my previous blog on big visionary dreaming?

All the best,

Susan

Make It True: Poetry from Cascadia, published by

Make It True: Poetry from Cascadia, published by